How to Build a Ship

Estimated Reading Time: 8 minutes

TL;DR

Inspired by last week’s blockage at the Suez canal, we have a nautically themed week here at Deep into the Forest. The subscriber issue on Tuesday covered the powerful China State Shipbuilding Corporation (CSSC), the world’s biggest shipbuilding company. By comparison to CSSC or other Asian shipbuilding giants, the American shipbuilding industry is much smaller, with only a fraction of the market share. The situation is distressing, since CSSC serves as a foundational backbone to PRC (People’s Republic of China) naval aggression, allowing the PRC to rebuild naval ships rapidly if needed. The CSSC recently demonstrated the ability to build a large oil tanker in 15 months, a pace that could also be applied to warships if needed (source). For comparison, US aircraft carriers currently take 5-10 years to build (source). The US needs to revitalize its shipbuilding infrastructure, either purely domestically, or alternatively in partnership with allies, to remain competitive with growing PRC naval might. Startups may be able to make a difference by commercializing rapid, large scale additive manufacturing of next generation ships.

A Quick Tour of Shipbuilding

Today’s issue explores how to build ships. Modern ships are giant machines, with the recently stalled Ever Given about the size of the Empire state building as shown in the tweet below.

Assembling structures at the scale of a modern ship requires heavy machinery. To get a quick sense of the shipbuilding process, watch one of these short videos, which respectively portray the assembly of a small Australian research vessel and a Canadian navy ship.

Heavy machinery such as large cranes and transporters are necessary, in addition to large shipyards, for assembling the ships themselves. Modern ships are massive multi-story constructions and are usually assembled block by block as shown in the videos above. Shipyards require machines capable of moving these extremely heavy ship blocks. Large cranes are used to move these ship blocks between different portions of the shipyard. The image below shows a large gantry crane used in a shipyard to move ship blocks.

While cranes suffice to move blocks across relatively small distances, at times ship blocks may have to be moved across longer distances. For these longer transport operations, shipbuilders use specialized shipyard transporters. These transporters are similar to transporters used to move extremely heavy spacecraft or other large pieces of industrial equipment.

Large ship blocks are typically carefully maneuvered together and welded together to form the finalized ship. For a more detailed overview of the full construction process, read this article or watch the time lapse video below showing a ship being constructed in a Romanian shipyard from start to finish.

Once a ship is fully assembled, it will still need to be tested in sea trials to make sure it is ready for the rigors of open water. Start to end, the full process takes between several months and several years.

Modern Shipyard Design

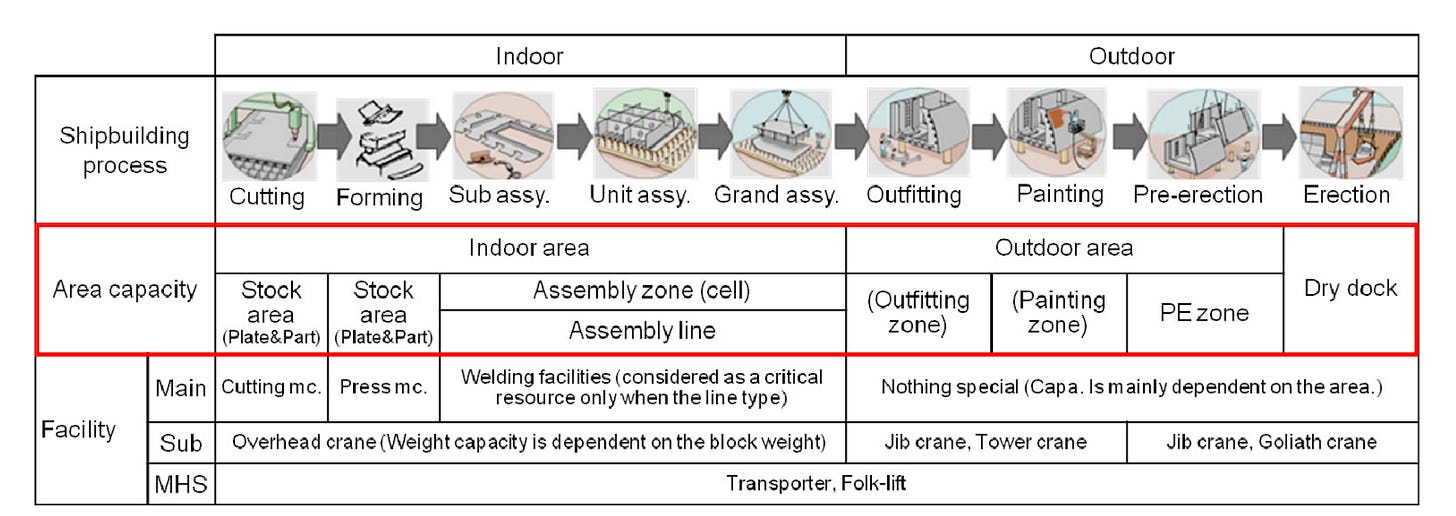

Modern shipyards have both indoor and outdoor infrastructure since ships are often assembled in pieces indoors and fitted together outdoors. Indoor assembly steps involve part cutting, part forming and different stages of assembly. Outdoor work involves steps like painting and structure erection. The table below walks through the steps in the shipbuilding process and where these steps typically occur in a shipyard.

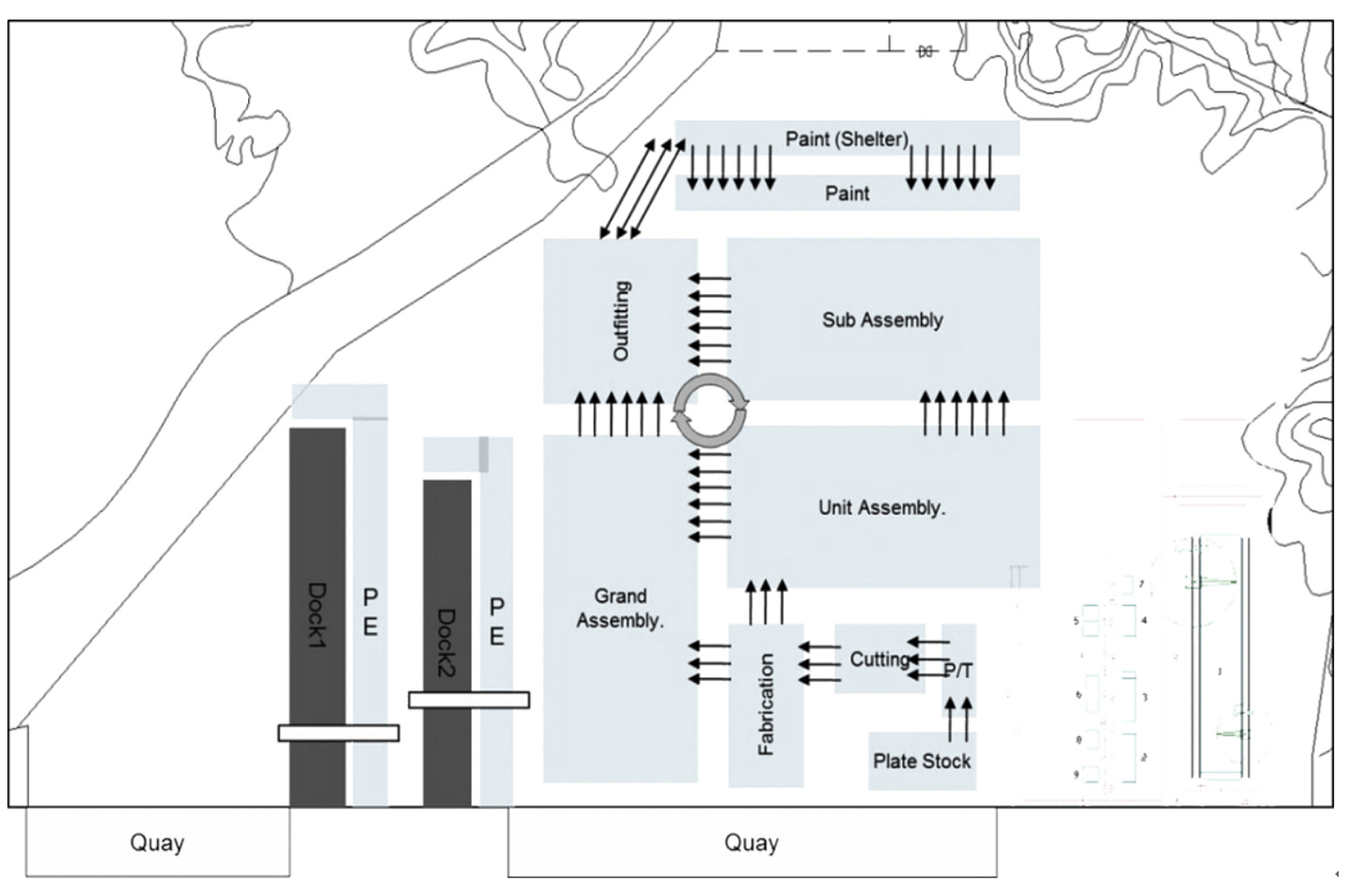

The shipyard itself needs to be located somewhere close to a body of water, perhaps a river or a bay, since the assembled ship will need to sail away from the shipyard. A large area of land will also be needed to build the assembly infrastructure needed for the shipyard. The diagram below represents the geometry of a hypothetical shipyard along with the movement of different components through the yard.

Potential Directions for Startups

Startups may be able to get a foothold in the shipbuilding industry by helping improve software tooling. Software tools for naval architecture, such as Orca3D, enable computational design of ships, but startups may be able to build slicker software tools that help eliminate redundancies in the process. The go-to-market process will likely be complex and require considerable domain expertise, but shipbuilding is a large market that is currently not served by many new startup players.

More ambitious would be to pioneer new methods to build ships more quickly. Additive manufacturing is starting to make waves in the shipbuilding industry and has been used to make parts of hulls, propeller blades and other components (source). The University of Maine has recently demonstrated a boat fully manufactured by 3D printing using one of the world’s largest 3D printers. The results are impressive, capable of building a large boat in a weekend! I recommend watching the full video below to understand how powerful additive manufacturing could be for shipbuilding.

At present, additive manufacturing techniques are new and far from the battle tested methods used to build large modern ships, but there may be a niche here for an ambitious startup to enter the field. Longer term, additive manufacturing could completely transform shipbuilding, allowing for extremely rapid manufacturing of large ships. In a future conflict with the PRC navy, large scale additive manufacturing could play a crucial role.

Discussion

For much of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st, American naval superiority has been a given. The PRC’s rapid naval expansion over the last decade, powered by CSSC’s commercial success, has started to change the status quo, with the PRC increasingly capable of contending with and even outdoing American naval superiority. Heightened competition makes the American shipbuilding industry increasingly important for national security. Unfortunately, American shipbuilding has been underfunded for decades and cannot currently compete with Chinese shipbuilders (or South Korean or Japanese shipbuilders for that matter). In a future naval conflict, the PRC navy could win simply by attrition if the US does not have its own infrastructure to replenish its fleet. Additive manufacturing techniques could allow US companies to catch up to CSSC’s domineering lead, but will require considerable research and development. Venture capitalists and research universities should direct funds towards next generation naval manufacturing to ensure that the US shipbuilding industry can compete with CSSC and other players.

Next week, we will return to computing with issues on quantum computing, but will continue to discuss shipbuilding in future Deep into the Forest issues.

Highlights for the Week

https://www.wsj.com/articles/graphene-and-beyond-the-wonder-materials-that-could-replace-silicon-in-future-tech-11616817603: Graphene is making waves in the semiconductor industry. It’s likely years out yet from consumer devices, but graphene’s low power dissipation could enable deep stacking of processor logic as we discussed in an earlier subscriber issue.

Subscription, Feedback and Comments

If you liked this post, please consider subscribing! We have weekly subscriber-only posts on Tuesdays.

Please feel free to email me directly (bharath@deepforestsci.com) with your feedback and comments! In particular, if you’re currently working in the semiconductor or battery industry, please get in touch! I’d love your input for future iterations in our semiconductor series.

About

Deep Into the Forest is a newsletter by Deep Forest Sciences, Inc. We’re a deep tech R&D company specializing in the use of AI for deep tech development. We do technical consulting and joint development partnerships with deep tech firms. Get in touch with us at partnerships@deepforestsci.com! We’re always welcome to new ideas!

Credits

Author: Bharath Ramsundar, Ph.D.

Editor: Sandya Subramanian